Introduction to Literary Criticism Literary Theory

Literary theory, also known as critical theory or simply theory, forms the foundation of literary studies. It provides the concepts and assumptions necessary for interpreting texts. Theory defines what counts as “literary” and what criticism seeks to achieve. For instance, Aristotle’s ideas influence the way we talk about the “unity” of Oedipus the King, while Achebe’s critique of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is shaped by postcolonial theory. Though not always acknowledged, theory underpins all critical practice, and its role within academia continues to evolve.

Philosophical Roots of Literary Theory

The history of literary theory parallels philosophy, stretching back to Plato. In works like the Cratylus, Plato questioned the relationship between words and meanings, a concern revisited in modern Structuralism and Poststructuralism. While Plato doubted the natural link between words and reality, much of Western thought upheld the belief that literature mirrors objective truth. Up until the 19th century, art was widely seen as a faithful reflection of the real world.

Evolution of Modern Literary Theory

Modern literary theory emerged in 19th-century Europe. German higher criticism analyzed biblical texts historically, while French critics like Saint Beuve linked literature to biography. This view was challenged by Proust, who argued that art transforms life experiences. Nietzsche’s skepticism toward knowledge—his claim that facts exist only through interpretation—profoundly shaped modern theory, paving the way for ongoing debates in literary studies.

Traditional Criticism vs. Modern Theory

Before the rise of New Criticism in the United States, literary criticism focused on history, biography, morality, and aesthetics. Critics worked with a shared sense of the literary canon and its purposes. Literature was studied as a source of culture and morality. Modern literary theory, however, questioned these assumptions, shifting toward new interpretive frameworks that challenged established traditions.

Greek Critical Tradition – Plato

Plato, a disciple of Socrates, focused more on philosophy than literature but offered significant ideas on art. For him, art is twice removed from reality: objects are already imperfect copies of ideas, and art merely imitates these copies. He argued that poetry is dangerous, as it appeals to emotions rather than reason, fails to provide knowledge, and often lacks moral value. Plato criticized drama for using cheap techniques to win audiences and for presenting flawed characters that encourage negative behavior. He also rejected the pleasure of tragedy and comedy, claiming they misguide emotions. On style, Plato insisted that a speaker must have knowledge, natural talent, practice, logical order, and awareness of audience psychology.

English Critical Tradition – From Sidney Onwards

English criticism began in the Renaissance with Sir Philip Sidney’s The Defence of Poesie. This tradition evolved through Dryden in the Restoration, Pope and Fielding in the 18th century, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley in the Romantic period, and Arnold, Ruskin, Pater, and James in the Victorian era. Many of these critics combined literary practice with critical thought, blending classical traditions with innovative ideas. Their works ranged from defending literature’s value to shaping new genres and movements. By the Victorian age, criticism began transitioning from subjective and prescriptive approaches to the more independent and systematic methods that defined 20th-century theory.

Literary Theory as an Ongoing Process

The word “theory,” from the Greek theoria, means “a view,” reminding us that every theory provides only a perspective, not a complete explanation. While older movements like Deconstruction or the Leavis School have faded in influence, their ideas remain relevant. In the 20th century, Marxism, Feminism, and Postmodernism broadened literary studies into cultural studies, treating all human discourses as texts. These movements emphasized economics, gender, and the instability of meaning, reshaping how literature is analyzed. Today, literary theory draws on multiple disciplines—linguistics, anthropology, psychoanalysis, philosophy—making it an interdisciplinary field. Some theories rise in popularity while others decline, but all contribute to the dynamic landscape of literary studies.

What is Liberal Humanism?

Liberal Humanism is a philosophical and literary movement which places human beings and their capabilities at its center. It is grounded in the belief that human nature is fixed and constant, and that literature reveals these universal truths about humanity. The term gained currency in the 1970s when literary theory emerged as a distinct field, and critics began to describe earlier approaches as “theory before theory.” The word liberal in this context indicates that it is not politically radical, while humanism implies an emphasis on human values rather than Marxist, feminist, or structuralist perspectives. Thus, Liberal Humanism regards literature as timeless, universal, and concerned with human essence rather than political or ideological commitments.

Trace the Evolution of Liberal Humanism.

Liberal Humanism has its beginnings in the early nineteenth century with the rise of English Studies. Between 1930 and 1950, its principles became fully articulated, although they were later challenged by Marxism, Feminism, and other critical theories in the 1960s. Early proponents like F.D. Maurice argued that English literature connected readers to what is “fixed and enduring” in their national identity. Liberal Humanism also shaped the scientific, rational worldview of the modern West, encouraging belief in individuality, common human nature, and universal truth. Critics like I.A. Richards further developed methods such as “Practical Criticism,” which isolated the text from context, ensuring that meaning could be derived from the work itself without ideological bias.

Explain the Emergence of English as an Academic Subject.

Until the early nineteenth century, English was under the monopoly of the Church of England. At Oxford and Cambridge, only male Anglican communicants were admitted, while Catholics, Jews, and others were excluded. This changed in 1826 with the establishment of University College London, which opened higher education to a wider group of people. In 1840, F.D. Maurice, as professor at King’s College London, introduced the study of set texts, laying foundations for Liberal Humanist principles. However, it was Matthew Arnold who is traditionally credited with establishing Liberal Humanism as a critical framework. Later, I.A. Richards pioneered “Practical Criticism” at Cambridge, emphasizing close reading of texts without reference to history or context, which became central to English studies.

The Key Critics of Liberal Humanism and their Contributions.

The roots of Liberal Humanism can be traced to classical, Romantic, and Victorian critics. Aristotle, in Poetics, defined tragedy, the role of plot and character, and the concept of catharsis, establishing one of the earliest frameworks for literary analysis. Samuel Johnson advanced criticism further with works like Preface to Shakespeare, applying close scrutiny to literature beyond religious texts. The Romantic poets deepened critical thought—Wordsworth emphasized poetry as the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” while Coleridge in Biographia Literaria stressed imagination and language. Keats introduced the idea of “Negative Capability,” and Shelley highlighted poetry’s role in defamiliarizing the familiar. The Victorians, particularly Matthew Arnold, gave structure to English studies. Arnold introduced the Touchstone Method and argued for literature as a substitute for religion. In the twentieth century, T.S. Eliot contributed concepts like “impersonality,” “dissociation of sensibility,” and the “objective correlative,” which became central to literary criticism.

Describe the Ten Tenets of Liberal Humanism.

Liberal Humanism is guided by ten core principles, often called its tenets. Firstly, good literature is considered timeless and universal, transcending the conditions of its age. Secondly, the meaning of a literary text is believed to reside within itself, not requiring external context. Thirdly, texts should be studied in isolation, free from ideology or politics. Fourthly, human nature is seen as unchanging, and literature reflects recurring emotions and experiences. Fifthly, individuality is considered essential and innate, transcending social or linguistic influences. Sixthly, literature’s purpose is to enhance life, but in a non-political and non-programmatic way. Seventhly, form and content are fused organically within literature, not imposed externally. Eighthly, sincerity in language is valued, avoiding clichés or artificiality. Ninthly, “showing” through enactment is preferred over “telling” or abstract explanation. Finally, criticism’s role is to interpret the text for the reader, without burdening it with unnecessary theoretical frameworks.

Formalism

Formalism in literary criticism is a method of analysis that concentrates on the text itself, rather than the life of the author or the surrounding social, political, or historical contexts. The idea stems from the belief that the form of a literary work is inseparable from its content, and to separate the two would be misleading. Formalists aimed to establish literature as a discipline with its own scientific rigor by examining how form creates meaning and tracing the evolution of literary forms over time.

In simple terms, Formalists held that the proper focus of literary study should be the work itself. Art, according to this school of thought, is created by following particular rules and logics, and new artistic forms emerge as breaks from earlier conventions. The central task of the critic, therefore, is to analyze the specific features that make a literary work distinct from ordinary writing—what they termed its literariness.

The History of Formalism

Formalism was never a single unified school but rather a collection of approaches that emphasized form in different ways. In the United States and United Kingdom, it gained prominence through the “New Critics” such as I.A. Richards, John Crowe Ransom, C.P. Snow, and T.S. Eliot. On the European continent, Russian Formalism developed in Moscow and Prague with major figures like Roman Jakobson, Viktor Shklovsky, and Boris Eichenbaum. While Russian Formalism and Anglo-American New Criticism shared similarities, they evolved independently and diverged in significant ways.

By the late 1970s, Formalism lost favor as new approaches—such as Post-structuralism, Deconstruction, and Cultural Studies—began to dominate, emphasizing politics and social context. For a time, “Formalism” was used negatively, implying an overly narrow focus on the text. However, in recent years, as the dominance of postmodern approaches has waned, many scholars have begun revisiting Formalist methods and acknowledging their lasting value.

Russian Formalism

Russian Formalism emerged with groups like the Society for the Study of Poetic Language (1916) in St. Petersburg and the Moscow Linguistic Circle (1914). Its proponents argued that literature should be studied scientifically, with linguistics as a foundation. They emphasized that literature has its own history of formal innovation, independent from external conditions. Central to their belief was that form is not just an outer shell of content but an integral part of meaning.

Anglo-American New Criticism

New Criticism dominated mid-twentieth-century literary studies in the English-speaking world. New Critics promoted close reading, emphasizing the unity of form and meaning within the text while rejecting biographical or historical analysis. At their best, they produced brilliant and wide-ranging interpretations, but they were sometimes criticized for being overly rigid and ignoring broader contexts. Eventually, New Criticism gave way to more politically oriented theories. Yet in the current climate of literary studies, some of their more nuanced works are being reassessed for their enduring insights.

Key Proponents of Formalism

Among the most influential Formalist critics were Roman Jakobson, Viktor Shklovsky, and I.A. Richards. Jakobson, a member of the Moscow Linguistic Circle, sought to define “literariness” using linguistic theory, strongly influenced by Saussure. Shklovsky, a leading voice, introduced two key concepts: defamiliarization and the plot/story distinction. His essay Art as Device challenged prevailing views of literature as either political product or personal expression, instead highlighting the unique nature of literary language.

I.A. Richards was a pioneering figure in English literary criticism and a founder of New Criticism. His works, such as Practical Criticism and The Philosophy of Rhetoric, were foundational for modern literary studies, influencing semiotics, philosophy of language, and rhetoric.

Fundamental Principles

Formalism insists on the autonomy of the text, viewing it as art that must be studied on its own terms, free from external influences like the author’s biography or historical background. Every element of the text is considered integral, with form and content inseparably linked. Formalists stressed the importance of relationships between words, poetic devices, and literary techniques in shaping meaning. They also emphasized the unifying function of paradox, irony, and ambiguity, which create tension within the work.

Shklovsky’s concept of defamiliarization illustrates this well. He argued that everyday life makes us blind to the uniqueness of objects and experiences, but literature renews our perception by presenting the familiar in unfamiliar ways. This makes literature not only more interesting but also deeply meaningful.

Key Concepts

The first essential concept of Formalism is the distinction between literary and practical language. Poetic language differs from everyday communication, and this difference defines the autonomy of literature. Another central concept is defamiliarization, where literary works disrupt ordinary perception to renew how readers see the world.

Shklovsky’s plot/story distinction further underlines the importance of form. While the “story” refers to the chronological sequence of events, the “plot” is how those events are arranged in the text. This distinction highlights how meaning is created not only by what is told but by how it is told.

Another major concept is literariness, which, according to Jakobson, marks what makes a text literary. Formalists identified literary devices as the key carriers of literariness, treating them as structural elements that could be studied scientifically. Finally, Jan Mukařovský’s idea of foregrounding showed how literary language calls attention to itself, creating estrangement and deepening the reader’s engagement with the text.

Allegory

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (360 BC) illustrates how human perception is limited and filtered by experience.

Allegory can be historical or political, where characters symbolize real-life figures or ideas.

Examples include:

Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) — political idealism through fiction.

John Dryden’s Absalom and Achitophel (1681) — political allegory through biblical parallel.

Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) — a journey symbolizing moral and spiritual struggles.

Aesop’s Fables (610 BC) — human behavior represented through animal characters.

Everyman is a classic morality play using allegory to teach virtue.

Spenser’s The Faerie Queene blends moral, historical, and religious allegory in poetic form.

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is a satirical allegory critiquing Enlightenment thinking and politics.

Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) is a political allegory targeting Soviet Russia under Stalin.

Bricolage

Coined by Claude Lévi-Strauss in La Pensée Sauvage (1962), bricolage means creating using what’s at hand.

It refers to mixing and matching elements from different sources to make something new.

Widely seen in:

Popular culture (e.g., music videos, fashion, film).

War of the Worlds (H.G. Wells) has evolved into various modern versions.

Bricolage thrives on reinvention with available material, a hallmark of postmodern creativity.

Animal Farm as Allegory

Orwell satirizes totalitarianism, showing how revolutionary ideals can be corrupted.

Example: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” critiques the betrayal of socialist principles.

Characters like Napoleon (Stalin) and Snowball (Trotsky) reflect historical figures and their roles in Soviet history.

Carnival

Introduced by Mikhail Bakhtin, carnival represents the inversion of societal norms and hierarchies.

During carnival, the line between elite and commoner blurs, enabling free expression.

Example: In Brecht’s Galileo, scientific ideas are debated by commoners and nobles alike, challenging authority.

Dostoevsky’s Bobok also embodies this festive disruption of norms and voices.

Intertextuality

Julia Kristeva introduced the term in 1969, blending Saussure’s semiotics and Bakhtin’s dialogism.

It shows how texts reference, echo, or transform other texts.

Irony is often used alongside, bringing hidden meanings or critique, as seen in:

Socratic dialogues

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet or Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex

Irony reveals human flaws, making it central to satire and literary critique (e.g., Swift’s A Modest Proposal).

Simulation

Originating from Plato, the idea involves representing or imitating the real.

Postmodernism questions the distinction between real and simulated.

Representations can seem “more real than real” (hyperreality).

Films like The Matrix or The Truman Show explore simulated realities as metaphors for modern existence.

Pastiche

Fredric Jameson distinguishes pastiche from parody.

Pastiche imitates styles without mocking; it mixes genres without judgment.

Examples:

Nabokov’s Pale Fire — blends poetry and fiction.

Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman — merges historical fiction with metafiction.

A.S. Byatt’s Possession — blends myth, romance, and detective fiction.

Films like Pulp Fiction combine gangster narrative, dark comedy, and romance.

Unreliable Narrator

An unreliable narrator is one whose version of events is questionable or misleading.

This technique highlights gaps between appearance and reality.

Famous examples:

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw — narrative told through a governess’s ambiguous journal.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro — the butler Stevens masks his emotional truths.

Films like The Usual Suspects (Kevin Spacey’s character) and Kurosawa’s Rashomon show how narratives vary by perspective.

The device reveals how subjectivity, memory, and denial shape storytelling.

Narrative

A narrative is a structured story, told through prose or verse, involving characters and events.

Barthes notes that narrative is universal — present in myth, painting, cinema, etc.

Gerard Genette emphasized how narratives manipulate time through:

Order (chronology)

Duration (length vs. real-time),

Frequency (repetition).

Ulysses by James Joyce covers one day (June 16, 1904) yet spans hundreds of pages.

Its structure mirrors The Odyssey, drawing parallels between modern life and myth.

Narratology

Tzvetan Todorov coined the term in 1969.

It studies how stories are structured and told — the types of narrators, their perspectives, and storytelling techniques.

Milestones in narrative theory:

Aristotle’s Poetics — defines story structure (beginning, middle, end).

Fielding’s Joseph Andrews — calls fiction a “comic epic in prose.”

Henry James — emphasized how a story is told over what is told.

Wayne Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961) — explores narrative voice.

John Barth’s “literature of exhaustion” (1967) — suggests traditional forms are used up, urging experimentation.

Mieke Bal’s Narratology — expands on narrative elements and their functions.

Frankfurt School & Psychoanalysis

Frankfurt School: A group of German Marxist theorists interested in culture, society, and politics.

Key Influences: Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung.

Jacques Lacan

Major Work: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (Lectures).

Key Concepts:

Phallocentrism

Mirror Stage: The child sees its reflection and begins to form an identity.

Three Developmental Phases:

The Real

The Imaginary

The Symbolic

Builds on Freud’s Oedipus complex (seduction, primal, and castration phases).

Sigmund Freud’s Theories

Unconscious Mind: A foundational idea for understanding psychological depth in art and literature.

The Interpretation of Dreams:

Introduces dreamwork.

Condensation: One dream image carries multiple associations.

Displacement: The true subject is shifted to something else (metaphorically).

Oedipus Complex:

Controversial idea: every child desires one parent and resents the other.

Applied to literature, e.g., Hamlet:

Hamlet hesitates to kill Claudius because Claudius embodies Hamlet’s own suppressed desires.

Laura Mulvey & Slavoj Žižek

Laura Mulvey:

Known for the concept of the Male Gaze in film theory.

Slavoj Žižek:

Applies psychoanalysis, Marxism, and film theory.

Interprets culture and ideology through Freudian/Lacanian lenses.

Simone de Beauvoir

Key Work: The Second Sex (1949)

Famous quote: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”

Themes:

Myths and stereotypes about women.

Critique of patriarchal structures.

Discussed abortion rights and contraception.

Influenced later feminists like Kate Millett (Sexual Politics).

Betty Friedan

Key Work: The Feminine Mystique (1963)

Based on a survey of college-educated women.

Findings:

Women felt deeply unfulfilled despite “ideal” domestic lives.

These issues lacked a public voice or terminology at the time.

Book critiques:

The post-war ideal of the full-time homemaker.

The myth that women’s fulfillment comes only from motherhood and housework.

Focused on middle-class, suburban women in post-war America.

Helene Cixous, Laura Mulvey, Julia Kristeva

Explored language, psychoanalysis, and feminism.

Themes of female identity, semiotics, and subjectivity.

Elaine Showalter – Gynocriticism

Gynocriticism: Shift from studying women as represented by men to studying women as writers.

Focuses on:

Recovering lost women’s literature.

Studying women’s experience historically and culturally.

Challenging the male-dominated literary canon.

Affective Fallacy

Coined by: William Wimsatt & Monroe Beardsley

Published in: The Verbal Icon (1954)

Definition: A fallacy (critical error) of judging a literary work by the emotional effect it produces on the reader/audience.

Key Idea:

Confusing what a poem is with what it does emotionally.

Leads to impressionism and relativism.

Example:

Calling a film/book “gut-wrenching” or “tear-jerker” judges it by emotion, not form or technique.

Countered:

I.A. Richards (in Principles of Literary Criticism, 1923) valued emotional responses.

Wimsatt and Beardsley critiqued this view.

Contrast:

Aristotle’s “Catharsis” values emotional impact positively in tragedy.

But 20th-century critics argue emotion shouldn’t be the basis for literary evaluation.

Ambiguity

Popularized by: William Empson

Work: Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930)

Definition: A literary device where a word or expression holds two or more meanings.

Described As: “Witty and deceitful” by Empson.

Example:

Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass explains “slythe” as a portmanteau of “slimy” and “lithe”.

Changing Interpretations:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin:

Sympathetic term during American Civil War (1861–65).

An insult during Civil Rights era (1950s onward).

T.S. Eliot:

Called Hamlet the “Mona Lisa of literature” – deeply ambiguous.

Oscar Wilde’s Reading of Hamlet (De Profundis):

Hamlet is not a hero, but a spectator of his own tragedy.

His madness masks weakness; his doubt is from a divided will, not skepticism.

Intentional Fallacy

Coined by: Wimsatt and Beardsley

Definition: A fallacy/error of interpreting a text based on the author’s intention.

Key Argument:

Authorial intent ≠ Meaning or merit of the text.

Implications:

Challenges autobiographical readings.

Undermines fixed meaning based on creator’s background or purpose.

Shifts focus to the text itself, not its origin.

Related Critical Ideas

New Criticism:

Emphasized close reading and the text itself.

Influenced by Wimsatt, Beardsley, Empson.

Jacques Derrida (1967):

In Writing and Difference, argues difference is essential to literary meaning.

Supports ambiguity as integral to language and literature.

Archetype

Definition:

An archetype is an original pattern or prototype that represents the most typical qualities or characteristics of a class or type.

Origin:

From Greek philosophy — ideas of beauty, truth, goodness, and justice as ideal forms.

Used in:

Archetypal Criticism (a form of literary criticism).

Function in Literature:

Archetypes help in identifying recurring characters, themes, and narrative patterns across cultures and time.

Examples of Archetypes:

Damsel in distress – e.g., Rapunzel

Femme fatale – a seductive woman who leads men to danger

Don Juan – archetypal womanizer or philanderer

The Quest Motif – hero goes on a journey (e.g., Frodo in The Lord of the Rings)

Redemption Ritual – a character atones through suffering

Key Text:

The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell

Explores universal myths and the hero’s journey (monomyth).

Allusion

Definition:

A brief reference to a person, event, place, or text from history, literature, mythology, or religion.

Purpose:

Creates depth by connecting the present text to cultural memory.

Depends on shared knowledge between the author and reader.

Often used to place a work within a literary tradition.

Types of Allusion:

Literary (e.g., referencing Shakespeare, Dante)

Historical (e.g., the French Revolution)

Mythological (e.g., references to the Odyssey)

Religious (e.g., biblical allusions)

Examples of Allusion:

1. Geoffrey Chaucer – The Canterbury Tales

Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale alludes to:

Petrarch, who adapted Boccaccio’s story of Patient Griselda.

Chaucer credits “Fraunceys Petrak” in the Clerk’s Prologue: “Fraunceys Petrak, the laureate poet…”

2. T.S. Eliot – The Waste Land

Full of classical and literary allusions:

Shakespeare (Antony and Cleopatra), Dante, Frazer, etc.

Purpose:

Not to show off, but to assert literary tradition.

Connected to Eliot’s essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” – a modern poet must write within tradition.

3. Modern Examples:

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Coen Brothers, 2000)

Alludes to Homer’s Odyssey.

No Country for Old Men (Cormac McCarthy)

Title is an allusion to W.B. Yeats’ poem Sailing to Byzantium: “That is no country for old men…”

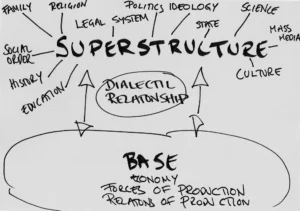

Base and Superstructure (Marxist Theory)

Origin:

A Marxist concept central to understanding class, ideology, and cultural power.

Definitions:

Base (Infrastructure):

Refers to the economic foundation of society.

Includes:

Means of production (factories, land, capital, tools).

Relations of production (relationship between bourgeoisie and proletariat).

Controlled by the bourgeoisie, who exploit the proletariat (working class).

Superstructure:

Built on top of the base; includes institutions and ideologies.

Examples:

Religion, Politics, Education, Family, Law, Mass Media, Literature.

Its role: to legitimate and maintain the base by reinforcing bourgeois ideologies.

Key Idea: The base determines the superstructure, and the superstructure justifies the base — helping to preserve the status quo.

Antonio Gramsci – Hegemony

Who:

Italian Marxist thinker and political theorist.

Key Concept: Hegemony

Definition: The dominance of a ruling class not just through force, but by gaining the consent of the subordinate classes.

Dominant groups (e.g., white, middle-class, heterosexual males) make their worldview appear universal and “natural”.

Subordinates willingly accept the status quo because they believe it benefits them.

Hegemony is sustained through culture, not just through coercion, but also through desire to belong.

Culture: A Contested Term

Key Thinkers:

Matthew Arnold – Culture and Anarchy (1867)

Culture = “The best that has been thought and said.”

Focus on refined, civilized values (elitist/classist approach).

T.S. Eliot – Notes Towards the Definition of Culture

Culture is more than survival; it includes aesthetic refinement (e.g., cuisine vs. just food).

“Culture is that which makes life worth living.”

Raymond Williams – Culture and Society (1958)

Critiques Arnold’s elitist view.

Views culture as ordinary – produced, circulated, and consumed by everyday people.

Emphasizes the role of literature and art in shaping and reflecting social values.

Adorno & Horkheimer (Frankfurt School)

Criticized mass/popular culture as a tool for ideological control (Culture Industry thesis).

Argued that culture can be used to manipulate and pacify the masses.

Popular Culture

Includes films, music, television, books, social media, etc.

Plays a crucial role in shaping modern identity, ideology, and public opinion.

Studied as a serious field in Cultural Studies, especially post-1950s.

Closure – Definition in Literary and Film Theory

What is Closure?

Closure refers to the sense of an ending in a narrative — where the plot is resolved, conflicts are settled, and the reader or viewer is given a feeling of finality.

In classic films, the literal card saying “The End” signifies this finality.

In literature, closure is traditionally achieved when:

Loose ends are tied up.

Characters reach their narrative destinies (happy or tragic).

A moral or emotional resolution is delivered.

Types of Closure

Closed Ending (Traditional Closure):

Provides a sense of completeness.

Reader/viewer knows “what happened” to the characters.

Often found in classical novels and Hollywood cinema.

Open Ending (Ambiguous Closure):

Leaves certain questions unanswered.

Reader/viewer must interpret the outcome.

Common in modernist/postmodernist literature and cinema.

Examples of Closure in Literature

Jane Austen’s Emma – Closed/Happy Ending

Final lines describe a wedding that is modest but joyful.

Despite the social criticism (from Mrs. Elton), the narrator affirms the perfect happiness of Emma and Mr. Knightley.

Sense of resolution, harmony, and restored social order.

Type: Traditional closure / Happy ending “…the wishes, the hopes, the confidence, the predictions… were fully answered in the perfect happiness of the union.”

Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence – Melancholic/Unfulfilled Closure

Newland Archer, now old, visits Paris but chooses not to reunite with Countess Olenska.

He sits in silence, watches the shutters close, and walks away alone.

There’s finality, but not fulfillment — closure through resignation rather than reunion.

Type: Bittersweet closure / Emotional restraint

“…as if it had been the signal he waited for, Newland Archer got up slowly and walked back alone to his hotel.”

Closure in Film

Classic films end with “The End”, reinforcing that balance has been restored and the story world is complete.

Modern and art films often avoid closure to reflect reality’s complexity, leaving endings open-ended or unresolved.

Why Closure Matters in Literary Criticism

Helps determine whether a narrative conforms to traditional structure or challenges narrative conventions.

Affects reader interpretation, emotional response, and the ethical/moral framing of the story.

Often discussed in narratology, structuralism, and postmodern theory.

Closure in Literature and Narrative

What Is Closure?

Closure = A sense of an ending, where the plot reaches resolution.

Classic works typically offer emotional and narrative finality.

Endings help restore balance, resolve conflict, and fulfill reader expectations.

Famous Ending Lines in Literature

Charles Dickens – A Tale of Two Cities

“It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

Spoken by Sydney Carton before his execution.

A heroic, sacrificial ending — tragic but redemptive.

Full closure with moral resolution.

George Eliot – Middlemarch

“Every limit is a beginning as well as an ending.”

Suggests cyclical continuity rather than finality.

Philosophical closure: endings are also transitions.

Edith Wharton – The Age of Innocence

Newland Archer sits in the dusk, watches the shutters close, and walks back alone to his hotel.

A quiet, melancholic closure.

No reunion, no high drama — but emotionally resonant finality.

Why Are Endings Important?

Frank Kermode – The Sense of an Ending

Endings satisfy our biological and cultural need for resolution.

Quote: “The end is a fact of life and a fact of the imagination… we live from the end even if the world should be endless. We need ends.”

Human beings make sense of life through structured narratives — we seek meaning in endings.

Aristotle and Classical Structure

In Poetics, Aristotle argues a plot must have:

Beginning (Exposition)

Middle (Complication)

End (Resolution)

Classical fiction generally follows this three-part structure.

Grand Narratives with Endings

The Bible:

Genesis → Apocalypse → Last Judgement

Karl Marx’s Das Kapital:

Primitive Society → Class Conflict/Revolution → Utopian Society

These “grand narratives” provide clear ideological and historical closure.

Fin de Siècle (End of the Century)

French term: End of the century (19th to 20th century)

Also known as the Decadence Movement

Major figures:

Oscar Wilde

Aubrey Beardsley

Théophile Gautier

Charles Baudelaire

Key Features:

Emphasis on:

Art for art’s sake

Melodrama, excess, sensationalism

Aestheticism & Symbolism

Mood: Decay, Ennui, Degeneration, Moral ambiguity

Modernism and Postmodernism: Changing Closure

In modern films and literature, “The End” rarely appears.

Writers/filmmakers play with narrative closure:

Endings are often open, ambiguous, or inconclusive.

Reflects:

Complexity of real life

Disruption of traditional storytelling norms

Reader/viewer interpretation over authorial control

What Is Postmodernism?

Postmodernism in literature is a reaction against realism and modernism. It:

Rejects singular truth and grand narratives

Embraces multiplicity, contradiction, and fragmentation

Seeks to challenge authority, including that of language, history, and meaning

Key Characteristics of Postmodern Literature

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Anti-realism | Challenges realism’s claim to truth or authenticity |

| Dialogic closure | Encourages open-endedness, interpretation, and multiple voices |

| Disarticulation & Fracture | Narrative breaks, gaps, disjointed forms to subvert coherence |

| Undecidability | No final or authoritative interpretation—multiple meanings persist |

| Chinese Box Structure | Layered, recursive storytelling (story within story); boundaries blurred |

| Apocryphal History | Rewrites or questions official history through alternative narratives |

| Science Fiction/Fantasy | Explores truth, reality, and identity in speculative frameworks |

Major Theorists and Their Contributions

Jacques Derrida – Deconstruction

Truth is not absolute but constructed.

Language is unstable and contextual.

Logocentrism (faith in reason/word as truth) is interrogated.

Deconstruction: Reading against the grain, showing contradictions within texts.

Fredric Jameson – Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Postmodernism reflects consumer capitalism.

Describes the era’s pastiche: imitation without parody or critical edge.

Argues for the blurring of high and low culture.

Emphasizes recycling of styles—art has lost originality.

Linda Hutcheon – The Politics of Postmodernism

Highlights postmodernism’s self-conscious, self-contradictory, self-undermining nature.

Literature becomes a critique of itself, often with ironic distancing.

Intertwines aesthetics with political and cultural critique.

Key Concepts Defined

Pastiche: A stylistic imitation that lacks the satirical bite of parody; a copy of a copy.

Apocryphal History: Reinterpreting history outside the official narrative.

Deconstruction: Reading texts to show how meaning breaks down internally.

Undecidability: When texts refuse closure, resisting definitive interpretation.

Why It Matters

Postmodernism is a lens for critical reading:

Makes us question meaning, identity, and history

Encourages active interpretation—not passive consumption

Offers tools to analyze how media and literature construct reality

Phenomenology in Literary Theory

Definition & Etymology

Phenomenology comes from Greek:

Phainomenon (φαινόμενον) – “that which appears”

Logos (λόγος) – “study” or “reason”

So phenomenology is the study of things as they appear — not as they objectively are, but as they are perceived.

Core Idea

Meaning is not inherent in objects or texts, but is created through perception.

It centers the perceiver — the reader, observer, or conscious subject.

Emphasizes that consciousness shapes meaning.

Thus, subjectivity becomes essential in interpreting literature or experience.

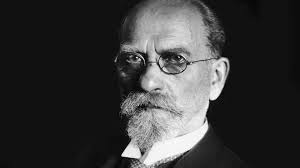

Founder: Edmund Husserl

Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) is the father of phenomenology.

Argued that philosophy should focus on consciousness, not external realities.

Wanted to bracket (set aside) assumptions about the external world and study pure experience.

Saw perception as a constructive act, not passive reception.

Key Shift in Focus

| Traditional View | Phenomenological View |

|---|---|

| Focus on object/text | Focus on perception of object/text |

| Meaning is fixed | Meaning is created through consciousness |

| Reader is secondary | Reader is central to meaning-making |

Major Thinkers Who Expanded Husserl’s Ideas

| Thinker | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Martin Heidegger | Introduced Being and Dasein (being-in-the-world); emphasized interpretation as fundamental |

| Hans-Georg Gadamer | Developed philosophical hermeneutics — meaning arises through dialogue between text and reader |

| Roman Ingarden | Applied phenomenology to literature; emphasized the incompleteness of texts, completed by readers |

| Wolfgang Iser | Co-founded reader-response theory; developed concepts like “implied reader” and gaps in the text |

| Hans Robert Jauss | Introduced horizon of expectations — meaning depends on cultural and historical context of the reader |

Phenomenology in Literary Theory: Reader-Response Criticism

The most visible impact of phenomenology in literary theory is through reader-response criticism.

Reader-response theory holds that:

A text has no meaning without a reader to activate it.

Meaning emerges through a transaction between the text and the consciousness of the reader.

Example Application

A novel like The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro doesn’t “mean” something objectively — instead, meaning is constructed differently by readers based on their experiences, perspectives, and emotional responses.

Summary: Why Phenomenology Matters in Literary Theory

Centers consciousness and perception.

Highlights that reading is a dynamic process.

Helps explain how and why different readers interpret texts in different ways.

Forms the foundation for many postmodern and deconstructive approaches to literature.

Hellenistic Age Literary Criticism: Horace & Longinus

Focus Period: 323–31 BC (Post-Alexander to Early Roman Empire)

Historical and Literary ContextThe Hellenistic age began after Alexander the Great’s death (323 BC). Eastern regions became centers of political, commercial, and cultural activity.

Prominent poets:

Callimachus and Philetas (Elegies & Epigrams)

Theocritus (Pastoral poetry)

Philostratus (Stoic influence)

Rise in technical literary criticism, rooted in Stoicism:

True happiness = moral/intellectual perfection.

Introduced six stages of literary learning, from reading aloud to poetry criticism.

Emphasized imagination (phantasia).

Horace (65–8 BC)

Son of a freed slave; educated in Rome and Athens.

Served under Brutus; later returned to Rome under Emperor Augustus.

Commissioned to write Carmen Saeculare (hymn).

Leading poet of Augustan Rome.

Key Works:

Odes, Epistles, Satires, Epodes, Ars Poetica

Satires: Described as “sermons” or “conversations”, often gentle and witty.

Ars Poetica (19–18 BC): A prescriptive poetic manual, framed as a poetic epistle to the Piso family.

Horace’s Core Critical Ideas:

“Instruct and Delight” — poetry should be useful and pleasurable.

Brevity aids clarity and memory.

Fiction must stay grounded in reality to be effective.

Form and genre should match — e.g., iambic meter for drama.

Emphasizes decorum, tradition + innovation, and emotional restraint.

Despised illiterate playgoers and believed theatre could corrupt morality (similar to Plato and Ovid).

Horatian Ode & Satire

Horatian Ode:

Lyric poetry in 2- or 4-line stanzas.

Influenced by Greek meters (Pindar), but more intimate, reflective.

Tone: Serious, ironic, melancholy, gently humorous.

Admired during Neoclassicism for technical mastery.

Horatian Satire:

Gentle correction via wit and humor, not harsh invective.

Critiqued Roman society with charm and humanity.

Influenced:

Alexander Pope, John Dryden, Nicolas Boileau

Comedy of Manners, Jane Austen, Cervantes

Longinus – On the Sublime

Likely written in 1st century AD (authorship uncertain).

Emerged during:

Second Sophistic (27 BC – 410 AD): Return to classical models.

Neoplatonism: (e.g., Plotinus) Reconciliation of Plato + Aristotle; use of allegory and symbolism.

Definition of Sublime:

OED: Of exceptional quality, beauty, or grandeur.

Longinus: “Consummate excellence and distinction of language that transports the reader beyond themselves.”

Five Sources of the Sublime:

Great thoughts

Strong, inspired emotions

Figures of speech – e.g., polysyndeton (overloading with conjunctions for intensity)

Noble diction

Dignified arrangement of words

Longinus’s Warnings:

Avoid overusing metaphors (no more than 2–3 at a time).

Avoid immoderate emotions (emotion must be overwhelming, not chaotic).

Sublimity is ruined by vulgar diction:

Critique of Herodotus:

“Seethed” = unpoetic

“Wore away” and “unwelcome end” = vulgar, unworthy of tragic grandeur

Philosophy of Sublimity:

Sublime transcends correctness — unlike Horace’s focus on form and taste.

Resembles a spiritual eruption (compared to Mount Etna).

Realism preferred over fantasy:

Iliad = Sublime

Odyssey = Too fabulous

True sublimity is rare — lost in Longinus’s time due to materialism and hedonism.

Horace vs. Longinus —

| Aspect | Horace | Longinus |

|---|---|---|

| Goal of Poetry | Instruct & Delight | Elevate & Transport |

| Emotion | Measured, appropriate | Overwhelming, awe-inspiring |

| Diction | Clear, decorous, correct | Noble, elevated, never vulgar |

| Style Concern | Rules, tradition, genre-suitability | Grandeur, genius, originality |

| Failure to Avoid | Excess imitation, bad taste | Vulgarity, excess, flat emotion |

| Legacy | Neoclassicism, satire | Romanticism, aesthetics of genius |

Summary: Classical Literary Theory

Horace: Art as Instruction and Delight

Horace believed the poet’s goal is to instruct and delight.

Brevity is crucial for instruction, avoiding superfluous words that overwhelm the mind.

Fiction meant to entertain should still stay close to reality.

The poet who combines the useful and the pleasurable is the most successful.

Horace emphasized that poetry must affect the reader, guiding their emotions and morals.

His impact on literary criticism is second only to Aristotle, with influence noted by Dante and others.

Longinus: On the Sublime

Longinus, though of uncertain authorship (1st century AD), emphasized sublimity in expression.

Sublime writing stems from powerful emotions, noble diction, and avoiding vulgar language.

Word choice deeply affects tone; even one ignoble word can ruin an otherwise majestic passage.

Longinus believed great literature elevates the soul and that the aesthetic and the moral are linked.

Classical Athens: Foundations of Literary Criticism

Flourished between 507–400 BC as a democratic city-state.

Three major developments influencing literature:

The rise of the polis (city-state) and public education

Political and ideological conflict with Sparta

Panhellenism — which led to literary canon formation and standards of imitation (mimesis)

From Homer onwards, poetry held a public, educational, and moral function.

The chorus in Greek drama represented the community, reinforcing literature’s political role.

Aristophanes’ The Frogs (405 BC)

A comic play that critiques poets Aeschylus vs. Euripides.

Aeschylus = traditional values; Euripides = newer democratic, secular voice.

It highlights that poetry was a tool of ethical education in ancient Greece.

Suggests a literary-critical consciousness was already active in comedy.

Plato: Critique of Poetry

Plato (428–347 BC), student of Socrates, founder of the Academy, used dialogues to explore ideas.

Believed in Forms (ideal realities) like justice, beauty, and truth — only accessible through reason, not the senses.

Theory of Forms

The empirical world is deceptive; real knowledge comes only through reason and understanding the unchanging Forms.

Art and poetry imitate the world, which itself is an imitation of the Forms — thus, poetry is a copy of a copy and doubly false.

Poetry in The Republic

Plato argues in The Republic (esp. Book III and X) that:

Poetry can corrupt moral behavior, especially in the young.

Poets model improper behavior — like cowardice, drunkenness, etc.

Only poetry that encourages virtue, bravery, and civic order should be allowed.

Most poets should be banned from the ideal republic.

Drama is especially dangerous due to imitation; epic is more acceptable.

Genres of Poetry According to Plato

Narrative – the poet speaks in his own voice

Imitation – tragedy and comedy (more dangerous)

Epic – a mixture of both

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

People are like prisoners in a cave, mistaking shadows for reality.

Poetry, being imitation, offers shadows rather than truth.

The allegory illustrates how representation can be misleading, reinforcing Plato’s distrust of art.

Key Concepts Introduced

Mimesis (Imitation) — central to Greek literary thought and criticism.

Representation — how literature mirrors or distorts reality.

Art and Ethics — ancient critics believed literature had a moral responsibility.

Rationality vs. Inspiration — contrast between Socratic reason and the irrational, divine inspiration of poets.

Classical Theory – Aristotle and Poetics

Core Focus:

Key Thinker: Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

Primary Text: Poetics

Key Concepts: Mimesis, Catharsis, Tragedy, Plot, Character, Hamartia, Peripeteia, Anagnorisis

Mimesis (Imitation / Representation)

Mimesis is a central aesthetic and philosophical term in classical theory.

For Plato, mimesis was negative — art is a shadow of reality, far from the truth.

Aristotle refuted Plato, defending literature as a medium to represent universal and eternal truths.

Humans are naturally imitative; imitation is how we learn and derive pleasure.

Art imitates life through different forms, mediums, and moral behaviors.

Example: Shakespeare’s Hamlet echoes mimesis — “to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature…”

Catharsis (Emotional Purification)

Borrowed from medical terminology; refers to cleansing or purgation of emotions.

In tragedy, the arousal of pity and fear leads to catharsis in the audience.

Tragedy moves the audience emotionally and morally, leading to emotional release and clarity.

It’s not a moral lesson, but a psychological and aesthetic experience.

Aristotle’s Definition of Tragedy

“Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude…”

Must be written in embellished language, presented in dramatic (not narrative) form.

Aim: to arouse pity and fear, leading to catharsis.

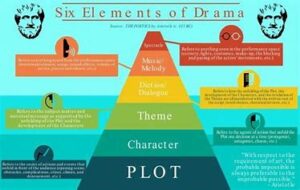

Six elements of tragedy:

Plot, Character, Thought, Diction, Melody, Spectacle.

Structure of Plot

Most important element of tragedy.

Must have unity: beginning → middle → end.

Based on causality (cause-effect logic).

A good plot includes:

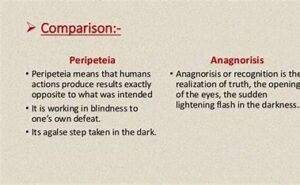

Peripeteia: Reversal of fortune

Anagnorisis: Recognition or discovery of truth

Pathos: Suffering

Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex is Aristotle’s ideal tragic plot — tight structure, intense emotional arc.

The Ideal Tragic Hero

A man of eminence and stature (e.g., king, prince).

Must be essentially good, morally upright, and consistent in character.

Cannot be a villain or of low social standing (common man as tragic hero is a modern idea).

Tragic downfall comes not from evil, but from hamartia (tragic flaw or error in judgment).

Examples of Hamartia:

Oedipus: impulsive, ignorant of truth

Antigone: defiant of state laws

Hamlet: procrastination

Othello: impulsiveness, jealousy

Legacy and Influence

Poetics remains the most influential treatise in literary criticism.

Elevated poetry as a form of knowledge, akin to philosophy.

Shifted poetry’s purpose from ethics to aesthetics.

Introduced universal principles for analyzing drama and literature.

Classical Literary Theory: Plato, Aristotle, and the Greek Context

In Classical Athens (507–400 BC), a democratic city-state that laid the intellectual foundation for Western literature, politics, and aesthetics. Three major historical and cultural developments shaped the evolution of Greek literature and criticism:

The Evolution of the Polis (City-State):

Literature—especially drama—reflected the collective values of the polis. The Greek chorus, for instance, often represented the voice of the community, underscoring the civic function of art.

The Ideological Conflict Between Athens and Sparta:

The political and philosophical rivalry between these city-states influenced thinkers like Plato, whose literary theories respond to the tension between democratic and oligarchic ideals.

Panhellenism:

A cultural movement that promoted unity among Greek city-states by standardizing literary ideals and establishing a canon of “classics.” This period saw the rise of mimesis (imitation) as a central concept in both literature and criticism.

Plato’s Literary Philosophy

Plato (428–347 BC), a student of Socrates, used dialogue and dialectical reasoning to pursue philosophical truth. His key contribution to literary theory lies in his Theory of Forms—the idea that absolute concepts like justice or beauty exist beyond the physical world.

According to Plato:

The empirical world is unreliable; true knowledge can only be attained through reason and an understanding of the eternal Forms.

Art and poetry are imitations of the physical world, which is itself an imitation of the ideal realm—making them a “copy of a copy.”

Because of this double remove from truth, poetry lacks epistemic value and can distort moral and civic behavior.

In The Republic (c. 360 BC), Plato outlines his critique of poetry and the arts:

Poets who depict gods in conflict or heroes in grief may encourage similar behaviors in citizens and should therefore be censored or excluded from the ideal state.

Literature must have a moral and educational function; it should shape character, instill virtue, and support civic harmony—not merely offer aesthetic pleasure.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave illustrates this philosophy of representation: people mistake shadows (appearances) for reality, just as audiences mistake artistic imitations for truth. True understanding comes only by grasping the Forms beyond these illusions.

Theatre and the Question of Mimesis

By the late 5th century BC, theatre had become the dominant literary medium, blending elements of epic, lyric, and drama. While Socrates viewed poetic inspiration as irrational, Plato insisted that literature must be guided by reason and ethical responsibility.

This tension is captured in Aristophanes’ play The Frogs (405 BC), which stages a comic contest between two playwrights:

Aeschylus, representing traditional moral values

Euripides, associated with newer, more secular and democratic ideals

The play underscores the civic importance of poetry in shaping cultural values, education, and public life—despite Plato’s skepticism

Aristotle’s Key Concepts in Literary Theory

Aristotle redefined literature, especially poetry and tragedy, as valuable modes of understanding universal truths, distinct from Plato’s moral suspicion of artistic imitation.

Mimesis (Imitation/Representation)

Unlike Plato, who viewed mimesis as a distortion of truth, Aristotle saw it as natural and fundamental to human learning.

Humans are the most imitative of creatures, he argued, and they derive pleasure and knowledge from representation.

Literature, especially tragedy, imitates actions and emotions, allowing audiences to grasp higher, often eternal, truths—not just historical specifics.

Catharsis (Emotional Purification)

One of Aristotle’s most influential ideas, catharsis refers to the emotional effect tragedy has on its audience.

Through feelings of pity and fear, viewers experience a cleansing or purification, leading to emotional clarity and moral insight.

The Structure of Tragedy

Aristotle identified six elements of tragedy:

Plot (mythos) – The most important element; it must be unified, causal, and complete (with a beginning, middle, and end).

Character (ethos) – The protagonist should be noble, morally good, and consistent, though flawed.

Thought (dianoia) – The ideas or themes expressed in the work.

Diction (lexis) – Language and dialogue used to express the thought.

Melody (melos) – Musical elements, often present through the chorus.

Spectacle (opsis) – The visual dimension of performance, though considered least important.

The Ideal Tragic Hero

Aristotle’s concept of the tragic hero is central to his theory:

A person of high status or eminence (e.g., kings, nobles).

Essentially good and morally upright.

Possesses a tragic flaw (hamartia)—a judgmental error or character defect that leads to downfall.

Evokes pity and fear through his/her fate, which is often undeserved but self-inflicted.

Examples include:

Oedipus (impulsiveness and ignorance)

Antigone (defiance of authority)

Hamlet (procrastination)

Othello (jealousy and impulsiveness)

Peripeteia and Anagnorisis

Aristotle further defined:

Peripeteia – A reversal of fortune, caused by the hero’s error.

Anagnorisis – A moment of recognition or realization about one’s own role in the tragic outcome.

These elements intensify the emotional impact of the plot and contribute to catharsis.

Aristotle’s Legacy in Literary Criticism

Aristotle’s Poetics is widely regarded as the most influential treatise in the history of literary theory. His ideas marked a shift from seeing poetry as moral instruction to understanding it as a form of aesthetic experience grounded in universal truths.

Unlike history, which recounts what happened, poetry deals with what could happen—what is probable and universal.

His systematic approach to plot, character, and structure continues to inform modern literary theory, drama, narrative studies, and film.

Early Modern Literary Theory: Humanism, Poetry, and the Defence of Art

The Early Modern Period—spanning the 15th to early 17th centuries—marks a vital transformation in Western thought, driven by Renaissance humanism, the rediscovery of classical texts, and the emergence of modern literary criticism. Poetry and rhetoric gained renewed prestige during this period as tools for ethical education, intellectual reflection, and emotional persuasion.

Humanism and the Renaissance Imagination

At the heart of this transformation was humanism, a philosophical movement rooted in the studia humanitatis—grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. Renaissance thinkers believed in:

The inherent dignity and potential of humans

The value of free inquiry and secular education

The emulation of classical Greek and Roman literature

Humanism emphasized that literature could shape virtue, stir imagination, and move audiences emotionally and morally. Art was no longer seen merely as divine inspiration or religious expression but as a human act of creation and imitation (mimesis).

The School of Abuse vs. An Apology for Poetry

A major flashpoint in early literary theory emerged with Stephen Gosson’s 1579 pamphlet, The School of Abuse, which criticized poets, musicians, and actors as “caterpillars of a commonwealth.” Echoing Plato’s suspicion of poetry, Gosson condemned the arts as morally corrupt and socially dangerous.

Ironically, he dedicated this attack to Philip Sidney—a celebrated poet, courtier, and scholar. In response, Sidney penned one of the most influential literary defenses in English: An Apology for Poetry (also published as The Defence of Poesy).

Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poetry: Key Arguments

Sidney’s Apology, written around 1581 and published posthumously in 1595, argues passionately that poetry is the origin, foundation, and summit of all learning. His central claims include:

Poetry is the oldest and most universal form of knowledge

“Poetry is of all human learning’s the most ancient… no learned nation doth despise it, nor barbarous nation is without it.”

Poetry predates other sciences and disciplines. It speaks across cultures and time, engaging both the educated and the “barbarous.”

The Poet is a Maker

Drawing on the Greek term poiein (“to make”), Sidney praises the poet not as a mere imitator of the world, but a creative force who shapes new worlds from imagination:

“The poet only bringeth his own stuff… and maketh matter for a conceit.”

Where other disciplines rely on the external world, the poet creates independently—elevating poetry above the empirical sciences.

Poetry Teaches and Delights

Sidney follows the classical Horatian ideal: poetry’s goal is both instruction and pleasure. He argues that poetry:

Inspires virtue through allegory and metaphor

Moves the soul through emotional and rhetorical appeal

Conveys universal truths more vividly than history or philosophy

Poets do not lie

In answer to Gosson’s charge that poets are liars, Sidney responds:

“The poet nothing affirms, and therefore never lieth.”

Poetry does not claim factual accuracy; it presents imagined truths in symbolic and rhetorical form—thus its value lies in moral resonance, not literal truth.

A Moral Art

Poetry’s moral function makes it superior to disciplines like history, which recounts events without inspiring virtue. Great poets do not corrupt, but guide the reader toward goodness.

Poetry, Rhetoric, and Renaissance Style

During the Renaissance, poetry was deeply linked to rhetoric, the art of persuasion. Writers like Sidney saw themselves as orators as well as artists, aiming to move audiences both intellectually and emotionally. This period witnessed a shift:

Away from medieval metrical forms

Toward classically inspired structure, emotional persuasion, and aesthetic grace

Legacy of Sidney and the Renaissance Critics

Sidney’s Apology stands alongside Aristotle’s Poetics and Horace’s Ars Poetica as a foundational text in literary criticism. It defines poetry not just as a source of beauty or pleasure but as a moral, philosophical, and civic force. It also laid groundwork for future literary theory by asserting:

The value of imaginative literature

The ethical role of the artist

The power of words to shape thought and virtue

The Early Modern Period witnessed the rebirth of poetry as a rational, moral, and imaginative art. While critics like Gosson attacked poetry’s social role, defenders like Sidney established its truth-bearing power, creative dignity, and universal value. His Apology for Poetry remains a timeless manifesto for why literature matters.

Classical Foundations: Plato, Aristotle, and Mimesis

Literary theory begins with the Greeks. Plato’s approach to literature is rooted in philosophy and ethics. He introduces the concept of mimesis (imitation), arguing that poets imitate reality and thus are twice removed from the truth. He is skeptical of poetry’s moral value, fearing its emotional sway over reason.

In contrast, Aristotle defends poetry, especially tragedy, in his Poetics. He regards literature as a natural human activity, valuable for its emotional and intellectual effects. Mimesis, for Aristotle, is a means of learning and catharsis. He emphasizes unity of action, plot structure, and character development, setting the foundation for dramatic theory.

Renaissance Humanism: The Rebirth of Poetic Authority

During the Renaissance, thinkers and writers re-engaged with classical texts but reinterpreted them through the lens of humanism and rhetoric.

Philip Sidney, in An Apology for Poetry, famously defends the moral and imaginative power of poetry. He asserts that poetry is the “most ancient” form of learning and not bound by empirical truth, but rather by creative construction and moral intent. Unlike history or philosophy, the poet “brings his own stuff” and transforms it into new meaning.

Poetry during this time was treated as a persuasive, rhetorical art designed to move the audience — merging beauty with moral instruction, echoing Cicero’s ideals of eloquence and virtue.

Neoclassicism: Order, Reason, and Elegance

Emerging in the 17th and 18th centuries, Neoclassicism looked back to classical antiquity — especially Aristotle and Horace — but interpreted through the lens of Enlightenment values: rationality, decorum, moderation, and adherence to nature.

Italian theorists like Castelvetro emphasized Aristotle’s unities of time, place, and action.

French critics institutionalized literary taste with the founding of the Académie Française in 1634.

Nicolas Boileau (Zola), in L’Art Poétique, formalized four principles of neoclassical literature: Nature, Reason, Decorum, and Unity.

In England, Alexander Pope was a leading figure. In An Essay on Criticism (1711), he stresses:

“First follow nature and your judgment frame / By her just standard, which is still the same.”

Pope and Dryden perfected the heroic couplet — a 10-syllable iambic form ideally suited for satire, drama, and moral instruction. Their verse embodied clarity, control, and intellectual rigor, rejecting sentimentality for balanced expression.

Cultural Context and Literary Practice

The coffeehouse culture of 18th-century London became a hub for literary discussion.

Neoclassicism favored urban themes, reflecting refined social life, over the emotional naturalism that would emerge in Romanticism.

Writers often sought patronage, positioning themselves within elite circles and aligning with classical ideals to elevate their art.

Despite admiration for Homer and other ancients, neoclassical writers recognized the difficulty of true imitation. They instead focused on lesser genres — satire, prose, and comedy of manners — executed with stylistic precision.

Neoclassical Literary Theory

Neoclassicism, flourishing in the 18th century—often called the Age of Reason—was a literary and philosophical movement that upheld order, rationality, and adherence to classical ideals. Deeply influenced by Greek and Roman traditions, this era emphasized restraint, decorum, and intellectual discipline in literary expression.

Key Figures

Notable contributors to this movement include John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, Samuel Johnson, and Lord Chesterfield. These writers were deeply committed to academic rigor, the study of classical models, and a respect for established norms.

Core Principles

Imitation: Central to neoclassical theory was the idea of mimesis—imitating nature and human action. But “nature” here meant a universal moral order, not simply the physical world.

Decorum: Writers were expected to match style, character, and content appropriately, maintaining harmony and propriety in all literary forms. This applied to language, structure, and genre use.

Reason Over Emotion: Emotion was not rejected but subordinated to reason. Clarity, logic, and balance were prized over excessive passion or personal subjectivity.

Impersonality and Universality: Literature should transcend the personal and subjective, instead expressing timeless truths about human nature and society.

Classical Forms: Instead of innovating new genres, neoclassicists often refined traditional literary forms—epic, satire, ode, elegy, tragedy, and comedy.

Stylistic Features

Language was polished, refined, and standardized.

Form was preeminent; writers favored structured poetic forms and valued harmony, proportion, and restraint.

Satire became a dominant mode, used to correct folly and vice with wit and moral insight.

Representative Works & Criticism

Dryden’s An Essay on Dramatic Poesy evaluated French vs. English drama, stressing Aristotelian unity and criticizing Shakespeare’s dramatic liberties.

Pope’s An Essay on Criticism and Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot blended poetic brilliance with moral and aesthetic judgment, showcasing the power of satire and wit.

Dr. Johnson emphasized the importance of a refined and universal vocabulary, aiming to elevate English prose and poetry beyond both colloquialism and technical jargon.

The Human Focus

Neoclassicists explored man in society, prioritizing universal human experiences over individual introspection. In Pope’s An Essay on Man, the famous line “Know then thyself” captures this preoccupation with human nature, morality, and rational understanding.

Early Romanticism and the Enlightenment Legacy

Historical Context (1760–1860)

This 100-year period was marked by two major events:

The French Revolution – introduced political upheaval and the questioning of authority.

The Industrial Revolution – transformed economies, work, and individual value.

Key features of the era included:

Emphasis on rationality, empiricism, and pragmatism.

Rise of political liberalism, individual utility, and belief in science and progress.

The Enlightenment (17th–18th Century)

A major intellectual and cultural movement in Europe that emphasized:

Reason and progress

Rejection of tradition, superstition, and clerical authority

Human rights, equality, freedom of thought, and religious tolerance

Scientific breakthroughs (e.g., Newton, Priestley) and political theory (e.g., Hobbes, Locke)

Key Enlightenment Figures:

England: William Godwin, John Locke, Francis Bacon

France: Voltaire, Diderot, Descartes

Germany: Leibniz, Kant

Netherlands: Spinoza

Voltaire’s Candide (1759) mocked rational justifications for war and inequality. Political philosophers like Hobbes (pessimistic view of human nature) and Locke (champion of liberalism) shaped modern democracy. In America, Jefferson and Franklin adopted Enlightenment ideals to draft the Declaration of Independence.

Women in the Enlightenment

Mary Wollstonecraft, a feminist and political radical, defended the French Revolution and demanded equal education and rights for women in her works:

A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

Criticism of the Enlightenment

Criticized for neglecting tradition, emotion, and subjective experience.

Adorno and Horkheimer (Dialectic of Enlightenment, 1940s) argued that overemphasis on reason led to dehumanization.

Immanuel Kant’s Contribution

Key Questions in Kant’s Philosophy:

What can I know?

What ought I to do?

What may I hope?

Kant tried to bridge reason and experience and defined Enlightenment as “release from self-incurred immaturity” i.e., the ability to think independently.

Major Works:

Critique of Pure Reason (1781) – Explores the limits and powers of human knowledge. He challenged a priori knowledge (knowledge without experience), arguing we cannot know the world purely through reason.

Critique of Judgment (1790) – Focuses on aesthetics, arguing that:

Aesthetic judgments are not cognitive but arise from the form of objects and their harmony with our imagination and understanding.

Introduces key concepts like:

Purposiveness: The perceived harmony between nature and our mental faculties.

Taste: The ability to judge based on this harmony.

Sublime: Unlike beauty (bounded form), the sublime involves boundlessness, evoking awe, admiration, and respect rather than charm.

Kant’s Legacy and Influence

Romanticism absorbed Kant’s ideas of imagination, aesthetic freedom, and the non-utilitarian value of art.

Influenced major thinkers and writers:

German Romantics: Goethe, Schiller

English Romantics: Coleridge, Edgar Allan Poe

Victorian Critics: Matthew Arnold

Modern/Postmodern Theorists: New Critics, Jean-François Lyotard

Kant emphasized the gap between the natural (sensory) world and the world of freedom (supersensible) — a philosophical tension central to Romantic and post-Enlightenment thought.

English and American Romanticism – Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Hazlitt

Historical & Intellectual Background

Timeframe of English Romanticism: 1789 (French Revolution) to 1832 (death of Sir Walter Scott)

A reaction against Neoclassicism, which emphasized decorum, order, and imitation.

Romanticism instead emphasized:

Spontaneity

Individual experience

Imagination

Emotional depth

Connection with nature

Dignity of the common man

Influence of the French Revolution

Ideals of liberty, equality, fraternity deeply influenced early Romantics.

Rousseau’s ideas (“Man is born free but everywhere in chains”) echoed in Romantic thought.

Disillusionment with the Revolution’s violence led poets like Wordsworth and Coleridge to salvage its original humanistic ideals through literature.

William Wordsworth (1770–1850)

Co-authored Lyrical Ballads (1798) with Coleridge — a turning point in English poetry.

Advocated for:

Simple, everyday language (rejection of “gaudiness and inane phraseology”)

Poetry drawn from “humble and rustic life”

Emphasis on emotional truth and natural speech

Belief that common people, women, and children deserve a central place in poetry

Definition of a Poet:

“A man speaking to men” – bridging the gap between poetic genius and reader.

Goal of Lyrical Ballads:

To make ordinary things appear extraordinary through the colouring of imagination.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834)

Major theoretical work: Biographia Literaria (1817)

Distinguished between Fancy and Imagination:

Fancy: Mechanical, dependent on memory, deals with fixities and definites.

Imagination:

Primary: Vital and unifying power

Secondary: Creative and synthetic, reconciles opposites (e.g., the general and the concrete, reason and emotion)

Source of true poetic genius

Key Terms in Coleridge’s Thought:

Synthetic power: Unifying opposites into an organic whole

Poetic genius: Linked to depth of imagination

Shakespeare: His model of the ideal genius — could become all things, yet remain himself

Example: “Kubla Khan” (1797)

A dream-inspired poem, incomplete yet visionary

Demonstrates Coleridge’s belief in poetry as imaginative transcendence, not mere realism

“He on honey-dew hath fed / And drunk the milk of paradise”

William Hazlitt (1778–1831)

Multifaceted: poet, painter, historian, critic

Influenced directly by Coleridge and the creation of Lyrical Ballads

Core Beliefs:

Imagination transforms reality through emotion and intuition

Advocated feeling over reason, aligning with Romantic ideals

In On Genius and Common Sense, emphasized:

“You decide from feeling, not from reason.”

Important Works:

An Essay on the Principles of Human Action (1805)

The Spirit of the Age (1825)

The Life of Napoleon (1830)

Key Critical Ideas:

Style and sincerity matter more than convention

Courage to say what one feels is essential for a true poet

There should be no gap between the man and the poet.

Together, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Hazlitt reshaped literary criticism and poetic creation by:

Celebrating emotion, imagination, and personal experience

Redefining the role of the poet and the purpose of poetry

Introducing the common man and natural language into literary prestige

Emphasizing sincerity, subjectivity, and poetry as a transformative force

Their legacy laid the philosophical and aesthetic groundwork for Transcendentalism in America and later literary movements worldwide.

American Romanticism

(The American Renaissance / Age of Transcendentalism)

Key Figures

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Henry David Thoreau

Walt Whitman

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Herman Melville

Edgar Allan Poe

Core Ideas and Themes

American Romanticism was a revolt against the Age of Reason, emphasizing:

Imagination, Individualism, Spiritual intuition, Nature as a refuge, Emotional intensity, Nonconformity, Subjectivity.

In contrast to the Age of Reason, which valued:

Rationality, Order, Control, Conformity, Mechanism.

Romanticism celebrated:

Spontaneity, Organic growth, Expression of individuality, The unique and eccentric.

Context and Background

The American Revolution and works like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776) contributed to a new national identity.

American Romanticism tied individual identity to national identity – a “poem waiting to be written.”

Major Writers and Works

Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

Works: Leaves of Grass, Song of Myself

Style:

Pioneer of free verse

Used colloquial language, realism, and inclusivity

Themes: Democracy, nature, equality (e.g., “What is the grass?”)

Celebrated individual identity and universal human connection

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882)

Major Essays: Nature, Self-Reliance, The American Scholar

Key Ideas:

Return to Nature

Childlike innocence reveals truth

Individualism and nonconformity are central

Mind and matter are linked by divine will

Self-Reliance: “Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist”

Rejected European tradition, unlike T. S. Eliot who embraced it

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862)

Major Works: Walden, Civil Disobedience (1849)

Themes:

Simplicity, solitude, spiritual unity with nature

Strong influence on Gandhi’s political philosophy

Quote: “That government is best which governs not at all”

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864)

Work: The Scarlet Letter

Work: The Scarlet Letter

Themes:Sin, guilt, redemption

Influenced by Coleridge’s imagination and Emerson’s ideas

Critic of industrialization and commercialism

Psychological and symbolic fiction rooted in American settings

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849)

Works: The Fall of the House of Usher, The Raven, Annabel Lee, The Tell-Tale Heart

Critical Essays:

The Philosophy of Composition (1846)

The Poetic Principle (1850)

Key Points:

Opposed allegory (unlike Hawthorne)