1. From Plate to the Sponge That Cleans the Plate: Understanding Ridge Gourd and Loofah

What if we told you that the same plant family can serve both as a healthy meal and as a natural cleaning sponge for your dishes? It sounds like something out of a sustainability fairytale, but it’s true. Welcome to the world of ridge gourd and loofah (luffa), two often-confused members of the gourd family that have very different endings. In this blog, we’re peeling back the layers to understand what sets these two apart and how they’re surprisingly connected.

What Is Ridge Gourd?

Ridge gourd, also known as Luffa acutangula, is a popular vegetable in many Asian cuisines. It’s long, dark green, and has distinct ridges running along its body, hence the name.

Key traits:

Soft, tender flesh when young

Mild flavor, absorbs spices well

Common in Indian curries, stir-fries, and soups

Packed with fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants

You’ll often see ridge gourd in markets labeled as “turai” or “beerakaya” depending on the region. It’s loved for its lightness and digestibility.

What Is Loofah (Luffa)?

Loofah (or Luffa cylindrica) looks quite similar when immature and is, in fact, also edible when young. But once it matures and dries out, it transforms into something very different: a natural scrubby sponge used for cleaning dishes or exfoliating skin.

Key traits:

Edible when young (though less common in cuisine)

When mature, the inner fibers dry into a sponge-like texture

100% biodegradable alternative to synthetic sponges

Grown in warm climates and harvested once the outer shell turns brown and crackly

So yes, that loofah hanging in your shower once grew on a vine, not in a factory!

Did You Know?

Loofahs are not made from the sea sponge! That’s a common myth.

You can grow your own loofahs at home and use them as natural scrubs.

Some farmers harvest luffa young for food and let others mature for sponge-making, a full-cycle use of one plant!

Ridge gourd and loofah show how versatile nature can be. One nourishes your body, the other helps you clean often from the same plant family, just harvested at different stages. Whether you’re slicing them for dinner or scrubbing your pans with them, these gourds prove that sustainability and simplicity can go hand in hand.

So next time you’re washing dishes with a loofah sponge, remember that could’ve been lunch!

2. Why Do Indians Laugh at Slang?

The Science, Culture, and Masala Behind the Chuckles

If you’ve ever burst out laughing after someone dropped a slang phrase like scene kya hai, baaga build-up ichestunnav ra, or dimaag ka dahi ho gaya, you’re not alone. Across India, slang isn’t just street talk, it’s storytelling, rebellion, performance, and connection. It makes people laugh not just because it’s funny, but because it hits something deeper; both in our culture and our brains.

Let’s unpack why slang makes us laugh, especially in the uniquely multilingual, dramatic, and expressive Indian context.

1. The Power of Mash-Up: Language Collisions are Inherently Funny

India is a multilingual playground. Most people grow up speaking at least two or three languages; and we love to mix them up. This fusion gives rise to slang that sounds clever, chaotic, and often hilarious.

For instance:

Jugaad lag gaya (a clever fix)

Scene kya hai? (what’s going on?)

Battery low aipoyindi (I’m exhausted from Telugu-English blend)

Mass look ichesav bey (You gave a killer look)

This sort of code-switching, where we jump between Hindi, English, Telugu, or Tamil within a sentence breaks the rigid structure of formal language. That break in rhythm surprises the listener and creates a sense of fun and play. It also reflects how people actually talk in real life, which makes it feel more alive and more laugh-worthy.

2. Slang Dares to Go There: Humor in Taboo-Breaking

Indian society often wraps itself in layers of formality and etiquette. Slang cuts right through. Whether it’s talking about sex (maal), anger (pichi pattindi), or class (chindi chor), slang often flirts with the forbidden.

In Telugu, someone might casually say:

Asalu comedy ayipoyav ra (You’ve become a joke)

Keka vesav (You nailed it)

Scene lu ekkuva ra nee life lo (You act like you’re in a movie)

The humor here often comes from shock value. These phrases are dramatic, cheeky, and sometimes outright rude but that’s the point. Using them in public, or in polite settings, adds a layer of social mischief. It makes people laugh because it feels a little dangerous and our brains love that.

3. Slang as Social Glue: It Bonds Us Instantly

Laughter isn’t just a reaction, it’s a signal. It tells the people around us: I get you. You’re my kind of people. Slang works in the same way. It creates an inside joke, a coded language between those who understand.

When someone drops a line like taggede le (I won’t back down) from Pushpa or Apun hi bhagwan hai from Sacred Games, the listener instantly feels the vibe. It’s not just a phrase, it’s a shared experience, a wink across the room. That sense of belonging and familiarity releases feel-good brain chemicals like oxytocin, and yes, makes us laugh.

4. Punching Up: Slang Mocks Authority and Pretentiousness

Humor often “punches up”, it mocks those in power or those who act superior. Slang is the perfect tool for that. Across India, you’ll hear phrases that roast self-important people:

Chamcha (sycophant)

Neta type (wannabe politician)

Angrez ban raha hai? (acting too foreign)

Baaga build-up ichestunnav ra (you’re hyping yourself too much)

This kind of sarcasm is like a verbal slap, sharp, funny, and satisfying. It makes us laugh because it exposes fake behavior in a way that feels clever, not cruel.

5. Our Brains Love the Drama

Indian slang isn’t subtle. It’s loud, exaggerated, and full of imagery and that’s exactly why it’s funny. Our brains are visual machines, and slang gives them something to play with.

Take these phrases:

Phat gayi (I got scared, lit. “It bursts”)

Dimaag ka dahi ho gaya (My brain’s turned to curd)

Comedy chesav ra (You made a fool of yourself, Telugu)

These phrases paint mental pictures, often ridiculous ones. That mental twist, saying one thing but imagining something wild creates cognitive dissonance, which is a known trigger for laughter.

Also, exaggerated emotion and theatrical delivery a hallmark of Indian conversation activate mirror neurons in our brains. When someone uses slang with full swag, tone, and body language, our brains “mirror” the performance, and we respond emotionally usually with laughter.

6. Pop Culture and Viral Energy: From Reels to Real Life

Slang spreads like wildfire thanks to movies, memes, and social media. Bollywood popularized phrases like:

Bhai kya vibe hai

Jhakaas

Apun ko kya

But Telugu cinema has its own cult classics:

Taggede le — Pushpa

Dimma tirigi mind block ayipothundi — Pokiri

Okkasari break isthe, life lo set aipothundi — Sye

These punchlines become part of our daily banter. When used in a conversation, they create instant comic timing, often enhanced by mimicry, exaggeration, or meme references. People laugh not just at the words, but at how they’re delivered with full filmy energy.

7. The Science of Laughter: What’s Happening Inside Us

Let’s not forget that slang humor also works because of how we’re wired. Here’s what’s happening in your body when you laugh at slang:

Dopamine: Released when something surprises or entertains you like an unexpected slang punchline.

Oxytocin: Strengthens bonds when you share a laugh or recognize a cultural reference.

Amygdala activation: Responds to taboo or risky content slang flirts with this constantly.

Mirror neurons: Make you respond to others’ expressions or tones which are dramatic in slang-heavy speech.

Visual cortex: Lights up when you hear vivid slang like brain’s become curd giving your imagination a nudge.

In short, slang doesn’t just tickle your funny bone, it fires up your whole system.

Why It Matters

Slang is more than just casual talk. In India, it’s a living, breathing, laughing organism born from the streets, shaped by movies, and turbocharged by memes. It’s local yet universal, playful yet powerful, and it reveals a lot about how we think, feel, and connect.

So the next time someone says baap kaun hai pata chalega, mass look ichesav bey, or battery low aipoyindi, don’t just laugh. Know that what you’re hearing is a brilliant blend of culture, biology, rebellion, and rhythm all packed into a few words.

3. From Missteps to Mastery: The Funny Side of Language Learning

Language is more than just a tool for communication, it’s a portal into the culture, humor, and history of a region. As someone who grew up speaking Odia, became fluent in Hindi and English, and then moved to Telangana after turning 30, I found myself embarking on the unpredictable and often hilarious journey of learning Telugu. While I can now speak the language comfortably, reading it is still a work in progress. But perhaps the most memorable part of the learning experience has been navigating the surprising and sometimes shocking similarities and contradictions between Telugu, Hindi, and Odia.

Learning by Comparison: My Natural Method

Every time I learned a new Telugu word, I instinctively compared it with my mother tongue, Odia, and the other languages I knew. This method made learning easier, but it also led to some laugh-out-loud moments and cultural surprises.

The Respect-Vulgarity Mismatch

Let’s start with one of my earliest and most unforgettable experiences: the word “రండి” (Rāṇḍi).

In Telugu, “Rāṇḍi” is a polite, respectful way to say “please come.”

But in Hindi and Odia, “Randi” is a vulgar term referring to a sex worker.

Imagine the shock on my face the first time I heard an elderly woman calling someone with a warm “Rāṇḍi!”, my mind went into instant panic mode until I realized the context.

Another example is “బండి” (Baṇḍi) in Telugu, which means “cart” or “vehicle.”

In Hindi, bandi often refers to a girl (“yeh meri bandi hai”, slang for girlfriend).

In Odia, it’s not a common noun but could easily be misunderstood due to its sound.

Together, hearing “Rāṇḍi, Baṇḍi vacchindi!” (Come, the cart has arrived!) sounded like something entirely inappropriate to my ears in the beginning!

Sounds That Mislead

Learning Telugu brought many such moments where my brain flipped back to Odia or Hindi and misunderstood harmless words. Here are a few more examples:

| Telugu Word | Meaning | Sounds Like in Hindi/Odia | Interpreted As |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheppu | Slipper | Hindi: “Cheppu” sounds odd or funny | Made me think of “chappal” (slipper) in Hindi |

| Pitta | Bird | Odia: “Pita” (father) | Confused me initially, why are they calling a bird ‘father’? |

| Kukka | Dog | Odia: “Koka” (brother to father) | Called a dog thinking I was calling brother of my father, awkward! |

A Humble Beginning with Humbling Lessons

When I first started speaking Telugu at local markets, auto stands, or with neighbors, I often mixed-up words, said things with the wrong intonation, or misunderstood jokes. But the people around me were patient, often amused, and always encouraging.

Over time, my vocabulary grew, and so did my confidence. But the laughter never stopped, thankfully, it just became shared. My family, especially my Telugu-speaking husband, still teases me about my early mix-ups, and I proudly own them.

Language and Love

Learning Telugu wasn’t just a necessity; it was an act of love. Love for my husband, for this land I now call home, and for the people who speak this language with such musical rhythm. Each misstep has brought me closer to understanding the culture, the humor, and the heart of Telangana.

Language learning is never a straight road. It’s full of twists, giggles, stumbles, and surprises, especially in a country as linguistically rich as India. For me, every word I’ve learned has been a bridge, sometimes rickety, sometimes poetic between my past and present, my roots and my future. And if a few words make you laugh or blush along the way, all the better. That’s where the real learning lives.

Money comes in various sizes, shapes, and materials across different countries around the world. In recent times, we’ve seen the rise of electronic money, UPI, Bitcoin, cryptocurrency, and more. Yet, no matter the form, money functions the same way everywhere, for transactions, purchases, spending, even for basic needs and desires. Simply put, from your first breath to your last, if you’re part of human society, you need to earn and spend money to survive.

As the years pass, we seem to become increasingly dependent on money. It’s a well-observed truth on Earth: the more money you have, the more affluent you’re considered. The more you accumulate, the more people tend to show deference or respect.

Let me take you back to the birth of currency in human society. It wasn’t possible for one person to produce all necessary goods, which led to the idea of exchanging one commodity for another. This eventually gave rise to a medium of exchange; currency. The barter system was the foundation of it all. In ancient times, people exchanged goods directly. However, as the inefficiencies of the barter system became apparent, societies began to prefer a standardized medium of exchange.

Anthropologists have documented numerous examples of primitive currencies based on commodities. These include cacao beans in ancient Mexico, cowrie shells in ancient China and India, tools, iron rings, and brass rods in parts of Africa, human skulls in Sumatra, woodpecker scalps among the Karok people of inland California, feathers in the Solomon Islands, dog teeth in Papua New Guinea, whale teeth in Fiji, strings of wampum beads in the American colonies, and even extremely large and heavy stone discs on the Pacific Island of Yap.

An important aspect to consider about the barter system era is that human needs were limited. People primarily focused on basic necessities and simple comforts. They had ample time to spend with their families and in nature. Mental health was generally better, with fewer asylums and hospitals, as illness was less common. Humans lived according to the natural purpose of life; much like other animals on Earth: eating, sleeping, reproducing, and doing only what was necessary to survive. This lifestyle resulted in minimal harm to Mother Earth.

Around 1200 BCE and onward, societies began using metals such as copper, silver, and gold as forms of money due to their durability, divisibility, and ease of transport. This shift marked a significant development from earlier barter and commodity systems. The first standardized coins are believed to have appeared in Lydia, in what is now modern-day Turkey, around 600 BCE. These coins were minted by King Alyattes using electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. The coins often bore symbols or images of rulers, which helped increase trust and legitimacy in their value and use, laying the foundation for modern monetary systems.

Paper money first emerged in China around the 7th century CE during the Tang Dynasty, when merchants began using promissory notes as a more convenient method of conducting large transactions. By the Song Dynasty, the Chinese government recognized the utility of this practice and began issuing official paper currency. The main advantage of paper money was its portability; much easier to carry than heavy metal coins, especially for long-distance trade. This innovation was so remarkable that the Venetian traveller Marco Polo famously documented the widespread use of paper money during his visit to China in the 13th century, introducing the concept to many in the Western world for the first time.

During the Medieval to Renaissance period in Europe, the development of banking and credit systems marked a major transformation in how economies operated. Cities like Florence and Venice became financial hubs, where institutions introduced innovations such as banks, bills of exchange, and credit mechanisms. These systems allowed merchants to engage in long-distance trade without carrying large amounts of physical currency, greatly facilitating commerce across regions.

In ancient India, temples were not only centres of spiritual life but also played a vital role in the economic and financial systems of society. They functioned as early forms of banks, especially during periods such as the Chola, Pandya, Gupta, and Vijayanagar empires. Temples received substantial donations in the form of gold, silver, coins, and land from kings, nobles, merchants, and devotees. These offerings were stored securely within the temple premises, making temples significant repositories of wealth. Due to their sacred status and moral authority, temples were trusted by the community as safe places for storing valuables.

In the 20th century, most of the world transitioned to modern fiat money; currency that has no intrinsic value but is accepted as legal tender because it is backed by government authority. A pivotal moment in this shift occurred in 1971, when the United States officially ended the Gold Standard, severing the direct link between paper money and gold reserves. This move solidified global reliance on fiat currency, which remains the standard worldwide today.

The 21st century has seen the rise of digital and cryptocurrencies, revolutionizing how people interact with money. Traditional payment methods such as credit cards, online banking, and mobile wallets have become commonplace. Meanwhile, the introduction of Bitcoin in 2009 signalled the beginning of decentralized digital currencies, forms of money that operate without a central authority. These innovations continue to reshape the financial landscape, presenting new possibilities and challenges for global economies.

In the journey of money, what humans lose and gain is worth noting. People have lost peace of mind, eyesight, hair, and above all, health and close friendships. On the other hand, people have gained money, luxury, greed, gluttony, and the so-called “better” way of living. It is widely assumed and experienced that those who have money can buy a good life; those with more money can buy anything on Earth; and those with even more can buy beyond Earth; even a space station.

If we closely study the past three decades, we see that many luxurious items, once only accessible to the rich, have become household goods. Take, for example, cameras in the 1980s or 1990s, which were typically found only in photo studios or in the hands of wealthy people. But by 2025, cameras have become commonplace in every household. With the advent of smartphones, from metropolitan cities to rural villages, from rags to riches, almost everyone owns one. The vast number of photos and videos on social media bears witness to the widespread use of smartphone cameras. What was once unavailable to the masses has become available to all, largely due to democracy and the increased accessibility of money in human society.

There are countless such examples: salt, sugar, mobile phones, drones, personal computers, laptops, internet access, flat-screen TVs, cars, air travel, refrigerators, washing machines, branded clothing, and shoes. The more money one has, the more things one can buy. But to be honest, the more money one has, the more they can extract and exploit the Earth. Wealth enables the purchase of gold, silver, diamonds, rubies, and other precious metals. The greed of the human species drives us to dig deeper and deeper into the Earth’s crust. I fear the day is coming when humans will drill from the North Pole to the South Pole just to extract more metals.

The Earth provides everything we need to thrive, yet we fail to seize any opportunity to protect it. Perhaps humans are the only species on Earth capable of bringing about their own doomsday. Our greed burns hotter than the fires of hell. Other species live out their natural cycles; birth, fulfilment of purpose, and death, but humans, endowed with intelligence, often use that intelligence against themselves. Every invention we create carries its own consequences. This reminds me of the story of Bhasmasura. It is not merely a myth but a truth: every human being on Earth in 2025 is like Bhasmasura, unknowingly bringing about their own destruction, not slowly, but prematurely.

Well, if someone murders another person, the law of the land punishes the culprit to maintain order in society. But what about the slow mutilation we continuously inflict on Mother Earth? Collective goals are easier to achieve than individual ones, and our shared harm to the Earth, our only home, is the perfect example of this. What punishment will we receive for breaking the laws of nature? In fact, some punishments are already visible in our lives, like the rising costs of health insurance.

Why do people buy health insurance? Because they expect to fall seriously ill one day, hoping the insurance company will cover hospitalization expenses. We pay these premiums every year, just in case. The same goes for life insurance, car insurance, and countless others. We work tirelessly for months only to see electronic money credited to our accounts. Then, with a single swipe on our mobile screens, that hard-earned money vanishes. We work for invisible money to afford visible things in life and put food on our plates. In earlier days, we could hold coins and notes in our hands and truly feel that we had earned something. Nowadays, we see only numbers on a screen, while we bow our heads to the grind for months and years forgetting even to breathe in nature for a moment. Trapped inside boxes called offices, we keep working endlessly.

I feel that the environment we have created for ourselves is much like the conditions once made for cattle. The mythological figure Mayasura feels strikingly real today. Mayasura is none other than our salaries; illusionary wealth that keeps us bound. The worst part is that we pass this same way of thinking to the next generation; our children. We proudly boast when our children stay far away from soil and dirt. Yet, the very essence of life is rooted in soil and water. How can we truly succeed if we never touch our feet to the roots?

The taller our buildings, the higher our reputation in society. This mindset, this perception, is what we continue to pass on to our children, hoping they will be successful. But who knows when we will change. Change is, after all, the very nature of life. I hope we can move toward a better future, with the goal of creating a healthier environment and a better Earth. The only true inheritance we can leave for the next generation is a healthy planet: clean air, pure water, and nutritious food on their plates. If we can achieve even this much in our lifetime rather than chasing after the illusion of Mayasura, we will have truly accomplished something meaningful.

The Politics of Nutrition: How Ads Overshadow India’s Food Wisdom

By Rupasri Pattanayak

Whenever we Indians speak of nutritious food, it is our traditional food that first come to mind. Historically, these foods were understood not merely as sources of energy but as a means to sustain health, balance, and well-being. The idea of nutrition in India has always been shaped by cultural practices, the principles of Ayurveda, religious influences, and the interplay between geography and agriculture. What we consumed was closely tied to what the land provided, the seasons dictated, and the body’s inner balance required.

Traditional Indian diets are usually vegetarian in many regions, driven by religion. Millets were consumed as the primary source of carbohydrates, and lentils were considered the main source of protein. Foods are chosen to the swing of the season: cooling foods such as ice apple, buttermilk, and cucumber in the summer season and warming foods such as sesame, clarified butter, jaggery, and peanut in the winter. In India, locally grown fresh food is valued more than processed food.

Our spices are more medicines, such as pepper, cardamom, turmeric powder, ginger, black cumin, cumin, long pepper, and carom seed, which are consumed to boost immunity, help in digestion, and prevent diseases. Culturally, we consume milk, curd, and clarified butter, which are considered complete foods and boost strength as well as immunity. Freshly prepared home-cooked meals are considered superior to preserved or packaged or canned or outside food.

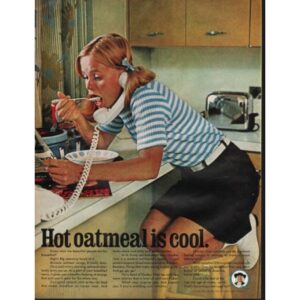

With all these nutrient-rich foods around us, the commercials nowadays popping up on our screens are to eat oats, as they’re healthy, full of fibre, good for digestive health, and what not. They display them on the silver screen in the name of selling the Western cereal in my country as if my country lacks superfoods.

Oats are not a grain that is historically or traditionally grown or consumed in India. For those who have weak digestion, oats can cause bloating and gas, as they’re heavy and slightly cooling in nature.

The slimy and sticky nature of oats can increase kapha if eaten excessively. Though nutrition-wise, oats are rich in beta-glucan, which is good for the heart and cholesterol. But Indian millets, such as pearl millets, finger millets, and barnyard millets, just to name a few, have more micronutrients, are naturally adapted to our climate and bodies, and offer better benefits.

If oats are cooked well with digestive spices such as cumin, black pepper, ginger, and cinnamon, then they can be alright for Indian-type bodies. The target buyers of oats in India are urban lifestyle folks who can’t always make fresh traditional breakfasts. For them, oats is a practical substitute. If prepared like the Indian way of preparing upma with veggies and spices, the western style of porridge with milk and sugar can cause sluggish digestion, diabetes, and obesity. Though oats are not the wrong food, they are not a natural part of Indian food wisdom.

Global food companies, such as Kellogg, Nestlé, and PepsiCo, and national food companies like Patanjali and Saffola spend crores on advertising to brainwash Indian minds, creating the idea that Western foods are superior. This is called nutrition versus the political economy of food. The taglines of western nutrition science, such as “cholesterol,” “fibre,” and “glycemic index,” are catchy terms that glue educated middle-class Indian minds. These catchy terms give the impression that traditional foods are outdated and western grains are more scientific.

It’s in the past century; to siphon off to their county, the Britishers encouraged cash crops instead of millets. We witnessed a decline in the production and consumption of millets. Millets were seen as poor men’s food, which actually needs less attention, less water, and less expense to produce in comparison to the cash crops. Later the green revolution focuses mainly on the production of wheat, rice, cotton, and sugarcane instead of bajra, jowar, foxtail millet, and kodo millet, all rich in fibre and minerals and ideal for Indian digestion.

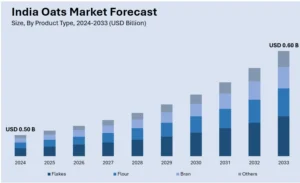

Oats in India are largely imported from Australia and Ukraine, which makes India dependent on foreign agriculture. The MNCs sell oats at premium prices, earning huge profit margins.

https://www.imarcgroup.com/india-oats-ma I

In Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755), his definition of “Oats” became legendary for its humour and national bias: “Oats: A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.” Though the definition was derogatory in nature, it showed the view of the people of England on oats in those bygone days. Health is not always about just fibre or cholesterol. It means digestion, mental calmness, immunity, and much more. A bowl of ragi mudde, bajra roti, or khichdi with clarified butter can do more wonders for the human body than a packet of instant oats.

Social Justice 2.0: Time to Revisit Reservations and Representation

India has constitutional commissions for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Women, Backward Classes, and Minorities but why not for Men or the Unreserved Category? India has established a series of constitutional and statutory commissions to protect and promote the rights of historically disadvantaged and marginalized communities. These bodies play a critical role in ensuring welfare, representation, and justice.

At the forefront is the National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST), both constitutional bodies functioning under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Enshrined in Article 338 and Article 338A of the Constitution, the commissions were granted constitutional status in 2004 after a long journey that began in 1978. Their mandate includes the protection, welfare, development, and advancement of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes across the country.

The second key institution is the National Commission for Women (NCW), a statutory body established on 31 January 1992 under the National Commission for Women Act, 1990. The NCW serves as the voice of women in India, addressing issues such as dowry, political representation, workplace equality, and the exploitation of women in the labour force. Its campaigns have often brought gender justice to the forefront of national debate.

Another crucial body is the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC). Originally set up as a statutory body in 1993 through the National Commission for Backward Classes Act, the NCBC was elevated to a constitutional body in 2018 through the 102nd Constitutional Amendment, under Article 338B. The commission advises the government on matters related to the socially and educationally backward classes and safeguards their rights.

Completing the list is the National Commission for Minorities (NCM), a statutory body under the Ministry of Minority Affairs. Established in 1993, the NCM is tasked with safeguarding the interests of India’s recognized minority communities, Buddhists, Christians, Jains, Muslims, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians. It addresses grievances, monitors welfare programs, and ensures equal opportunities for minority groups. Together, these commissions form the backbone of India’s institutional framework for social justice, equality, and inclusive development.

A growing demand in the dream of Vikshit Bharat is unfolding around the absence of similar institutions for Men and the Unreserved Category. The rising instances of false dowry and harassment cases, men’s mental health, gender biased competitions and reservations are largely remained unaddressed in India. Like National Commission for women, voices are emerging in demand of National Commission for Men.

Alarmingly, in recent years the cases which were registered where women have been implicated in the killing of newlywed husbands, which arises concerns about the absence of proper legal support for men.

- A Jaipur woman and her lover strangled her husband and disposed the mortal body in a cement drum, was viral online, drawing national concern.

- In June 2025, Sonam Raghuvanshi was arrested for orchestrating the murder of her husband in Meghalaya during their honeymoon.

The misuse of the legal provision of Section 498A & Alimony Laws.

- In August 2025, a Delhi court discharged a man and six relatives of alleged charges under 498A, dowry harassment, and sexual offenses, citing a lack of credible evidence and warning against overreach in applying criminal law to matrimonial disputes.

- In December 2024, the Supreme Court explicitly criticized the growing trend of weaponizing Section 498A for vendettas and emphasized the judiciary’s need to guard against such misuse.

- In 2021, 14.2 suicides per 100,000 were reported among Indian men, 2.5 times the rate for women. Leading causes included family disputes, ill-health, and unemployment.

The most contentious debates in India’s social justice landscape revolves around the reservation system. The cause for the reservation policy was noble and for a certain period was the target to implement. It played a vital role in uplifting historically disadvantaged groups but later it became a political strategy for vote banks, resulting brain drain. And the time has come to recognize the financial background as a key criterion for reservation, ensuring that the truly disadvantaged regardless of caste are not left behind.

Revisit the “Creamy Layer” Principle

- The current framework excludes the “creamy layer” from OBC reservations, but critics say this principle should be applied more rigorously across categories. Families that are already economically well-off should not continue to draw benefits intended for the underprivileged.

Supporters argue that without such reforms, the reservation system risks entrenching new inequities even as it seeks to correct historical ones. With the 16th Census scheduled for 2027, the government has an opportunity to rethink the reservation framework before fresh demographic data is collected. Experts argue that this is the ideal time to revisit the “creamy layer principle” and ensure that reservations continue to serve those who need them most.